SEAL SWCC COMBAT SIDESTROKE GUIDE

Inside the SEAL SWCC Combat Sidestroke guide are all-encompassing in-depth videos, photos, practice drills and detailed instructions on how to do it. The CSS is taught to all SEAL and SWCC candidates. There's no easy way to master it, and every Naval Special Warfare operator has to know it.

By: Naval Special Warfare

Posted: May 5, 2022

Related content:

If you find yourself swimming through the surf zone to a beach with 60+ pounds of equipment, your comfort level in the water or your ability to swim should be the last thing on your mind. The only thing you’re focused on then is the execution of the mission.

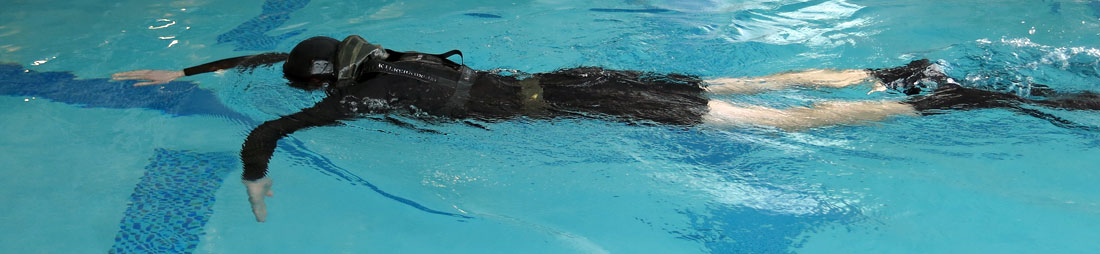

There's no easy way to master the Combat Sidestroke (CSS). It's is a variation of the sidestroke, freestyle and breaststroke all mixed together. The CSS is taught to all Sea-Air-Land (SEAL) or Special Warfare Combat Crewman (SWCC) candidates. This stroke allows you to swim more efficiently and reduces your body's profile in the water, thereby making you less visible during combat operations when surface swimming is required.

Swimming fundamentals

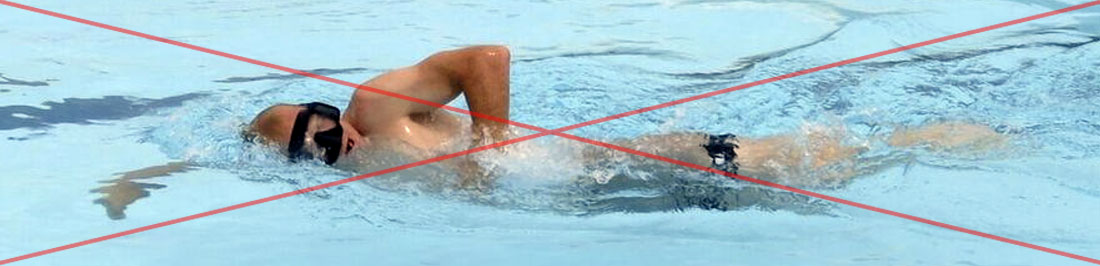

- Balance is key. Two elements affect your balance in the water: the head and lungs. Many swimmers, especially when using the breaststroke, will swim with their head up, which forces their hips to sink down. This position is like swimming uphill. But when your body is flat and parallel to the water-line, swimming is far more effective and you can swim comfortably.

- The taller the person, the faster they'll swim! It all has to do with drag. When a swimmer is fully stretched horizontally in the water, their body's drag is reduced and they can swim faster.

- Rotate from the hips. In baseball, when the batter swings the bat, they rotate their hips to increase the power of the swing. It works the same way in swimming. If you engage your hips and use the body's core muscles, it'll increase power.

HOW TO SWIM THE COMBAT SIDESTROKE

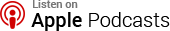

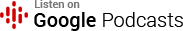

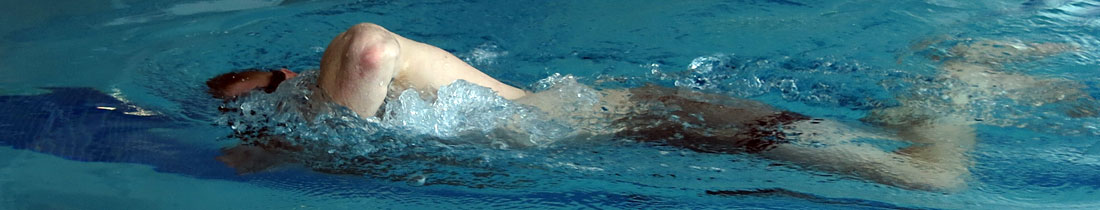

The CSS is a long axis tactical stroke designed to be low profile, efficient, and fast. It's used to travel long distances in open water and to quickly swim through the surf zone. The CSS is performed with a 90 degree balanced rotation. Begin the stroke on your stomach then onto your side and back to the stomach. All put together it is a natural rotation, using the core to assist and create power and torque.

Your starting and stopping point of the stroke cycle is in the streamlined position. The stroke begins with the pull arm. As you pull, you'll allow your shoulder and hips to open to the appropriate direction, allowing an opportunity to breath. When the pull arm begins the recovery, the kick (either scissor or flutter kick), will help facilitate your body’s rotation back into the streamline position. While in this streamline position just under the surface of the water, you're encouraged to exhale slowly, and flutter kick, especially with the use of fins. This will assist in a continuous and consistent forward motion.

Body position

You'll stabilize yourself by the alignment of your head, back, and hips. This is referred to as stabilizing the core. Stabilizing your core is the foundation of the CSS. You'll achieve this by beginning the stroke in the streamline position and ending in the same position. With continued alignment, the energy output is directed to forward movement and sidewinding is minimized.

| Body position | |

|---|---|

| Mistake | Correction |

| Head above the water a.k.a. swimming up-hill | Maintain a head down posture with head below the surface of the water, a.k.a. swimming down-hill |

How to do the catch and pull part of the CSS

Your top arm begins and ends in the streamline position. It is a cyclical pattern. At the top of the stroke (the longest body position), you press the palm of your hand down to begin the catch, continuing until a vertical forearm is achieved and the elbow is above the wrist.

You begin the pull sequence by following through until the hand is in line with your upper thigh and your arm is fully extended. You'll be on your side until recovery of the pull arm has begun. Immediately, as your hand comes in line with the thigh, the recovery sequence begins.

Streamline. Beginning of the swim.

Initiating the catch. Keep your fingers lower than your wrist, wrist lower than your elbow, and your elbow lower than your shoulder. This allows you to start anchoring your elbow to maximize the effectiveness of the pull arm.

Full catch. Position your arm to allow you to pull it over an anchored position. This maximizes the surface area of your arm, while also allowing you to utilize larger muscle groups for propulsion.

Full catch in the pull phase.

Full catch in an anchored position. Begin to breathe.

Recovery. Beginning the power pull.

Recovery finish. Start your scissor kick.

The end. Back to the streamline position.

| Body position | |

|---|---|

| Mistake | Correction |

| High or raised elbow in recovery a.k.a. sharkfin | Keep your following hand along the mid-line |

| Begining the recovery prior to the full range of motion a.k.a. half-pull | Keep your arm fully extended alongside your body |

| Not achieving a full extended streamline before starting your next arm cycle | Glide underwater for 2-3 seconds in a streamline position |

| Not rotating when pulling | Rotate your body and hips to create more power, similar to a baseball player throws with more power by using their core, hips, and shoulders |

| Hand exiting the water | Don't let it |

| Dropping your elbow in the initial catch position | Keep your hand below your elbow |

| Pulling your sculling arm to far back or under your body | Keep your hand in front of your body |

How to do the recovery part of the swim

Your arm will be fully extended; hand past your waist, along the side of your body when you begin the recovery. You'll begin the recovery process by moving your hand forward (hand and arm must be underwater) as close to your body as possible, from past the hips back to streamline.

During this phase, you'll rotate your shoulders and hips to move from your side into a streamline position and onto your stomach. You'll end in the same streamline position. By rotating the body when pulling, you'll become more efficient and powerful. This creates more torque as opposed to pulling with the arm only.

Recovery, beginning of the power pull.

Recovery. Good form. Note how low the elbow is.

Recovery. Bad form. The elbow is to high. This is called the "shark fin."

Form and function of the lead arm

The lead arm works independently from the pull arm. It's a supplementary movement to complete your swim rotation to the initial starting position, the streamline. When the pull arm is recovering and has begun moving forward from the waistline to the streamline position, the lead arm slightly presses down and makes a catch. The fingertips of the lead arm will rotate down with the palm pressing back as the elbow remains higher than the hand. This leads into a small sculling motion (this motion is almost identical to a breaststroke motion). The two hands will meet at or in front of your mask as you reach forward, placing you in the streamline position.

Lead arm catch.

Reach forward.

Reach to streamline.

A WRAP UP OF ALL THE STROKE ELEMENTS

Streamline.

Initiating the catch.

Anchor position.

Initiate power pull.

Beginning of recovery.

Begin to enter streamline. End recovery.

Streamline. End recovery.

Streamline. End recovery.

HOW TO GUIDE YOURSELF IN OPEN WATER

The guidestroke is used in conjunction with CSS during open water swimming to sight stationary objects to ensuring you swim in a straight line. The guidestroke itself is very similar to a breaststroke in that you are lifting your head and upper body out of the water. While the head is out of the water you'll sight on a stationary object, whether it's a buoy in the water or an object on land, the guidestroke helps you stay on course.

Body position

Stabilize yourself by aligning your head, back, and hips. This is known as stabilizing the core. Stabilizing the core is the foundation of the stroke. It's achieved by beginning the stroke in the streamline position and ending in the same position. With continued alignment, the energy output is directed to your forward movement and your sidewinding is minimized.

Streamline. Starting position.

Breaststroke pull

From a streamline position, your palms press out slightly wider than your shoulders. Continuously press your palms against the water. Rotate your hands so that the palms pull in towards your chest, finger-tips pointing down while maintaining a high elbow position. Pulling your arms towards your chest creates forward momentum which allows your chest to be angled up, and your head in place to breathe and guide.

Breaststroke pull. Initial catch.

Breaststroke pull. Initiating the catch.

Breaststroke pull. Initial breath and pull.

Breaststroke pull. Begin breaching the surface.

Breaststroke pull. Begin breaching the surface.

Breaststroke pull. Full breach.

LEARNING THE KICKS

Three types

- Dolphin kick

- Scissor kick

- Flutter kick

Dolphin kick

The kick used with the guidestroke is a dolphin kick. As your arms move forward, use both feet in combination to kick in a downward motion and drive your body below the surface of the water into the initial starting or streamline position.

Dolphin kick. Initital kick phase.

Dolphin kick. Power kick phase.

Dolphin kick. Ending into a streamline.

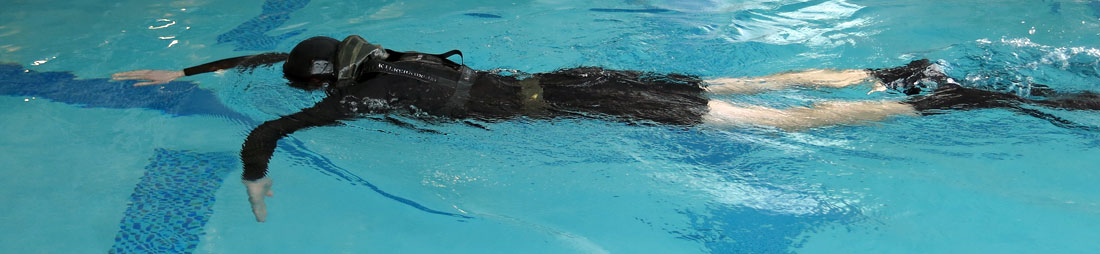

Scissor kick

You utilize the scissor kick in the combat sidestroke when not using fins. It may also be used in treading water training evolutions without fins. The scissor kick is a very powerful kick, but has a resting period when in the streamline position. To become more efficient, you can use a flutter kick until the next stroke cycle begins. Your legs work independently of each other. The top leg (the leg closer to the surface of the water) and the bottom leg (the leg furthest from the surface) move forward and backward respectively, and then meet back together in a streamlined position. Hence, the name of the kick, the movement resembles a pair of scissors.

| SCISSOR KICK | |

|---|---|

| Mistake | Correction |

| Top leg: pointing your foot, instead of keeping it flexed toward your shin | Draw your toes toward your shin throughout the kick until the streamline position |

| Bottom leg: dropping causing a breaststroke kick | Make sure both your legs are moving along the same plane (forward and back) |

Scissor kick. Knee drawn.

Scissor kick. Kick the legs outward.

Scissor kick. Feet return to the start position.

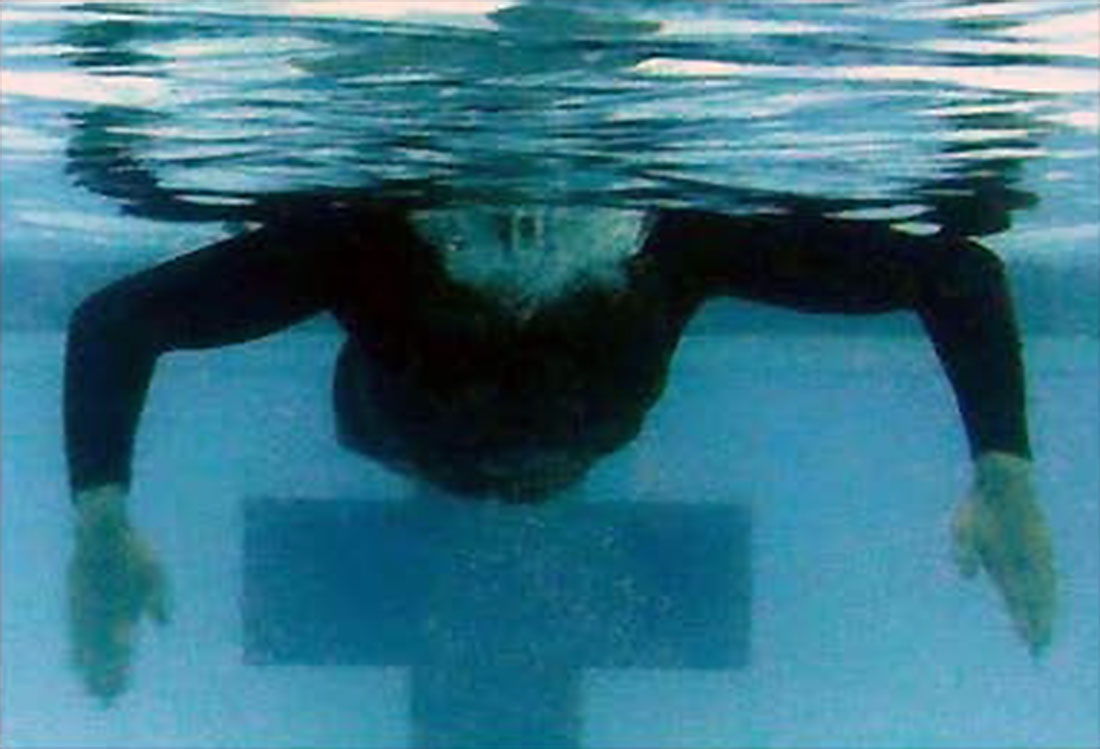

Flutter kick

The Flutter Kick is a continuous kick, resulting in a continuous forward motion. The kick is employed with or without fins. It's an integral part of CSS with fins, contributing to continuous speed and consistent power. The flutter kick is initiated from the hips, allowing the legs to move independently in an up and down motion. While your legs remain long and straight, this does not mean they are rigid. You must have a natural bend to the knee (a slight bend, nothing more) and a relaxed ankle, though the toes must be pointed behind you. This provides as much surface area as possible to the kick, resulting in a greater displacement of water and forward motion.

You'll kick your legs in an up and down motion; pushing the top of the foot down, and pulling the other foot up. Without fins, the kick has a smaller range of motion and is much faster. The kick without the use of fins should occur around fifteen times every ten seconds. When fins are utilized, the rate of the kick will slow slightly, and the range of the kick will become slightly bigger. It's imperative that you don't disturb your natural body alignment with the gait of the kick.

| FLUTTER KICK | |

|---|---|

| Mistake | Correction |

| Kicking with your foot in a natural flat footed position | This limits the surface area for the kick, which in some cases leads you to sink. Point your toes as if punting a football |

| To large of a kick | You should imagine kicking within a 1.5 foot by 1.5 foot box |

| Feet out of the water, excessive splashing | Only allow the bottom of your foot to meet the surface of the water |

| Bicycle kick | This occurs when your kick is initiated from the knee. Your kick should begin with your hip and only a slight natural bend to your knee |